Barbican Gallery, London

Born into a family of acting professionals and having grown up backstage at the Reykjavik City Theatre, Kjartansson’s work combines his experience of stage traditions with experiments in repetition and endurance. Clichés and motifs of Western culture, romantic melancholy and even his own conception, provide the personal and often playful subject matter of the artist’s emotionally charged work. Having successfully represented Iceland at the 2009 Venice Biennale and participated in 2013 with standout works, Kjartansson is now at the cutting edge of contemporary performance art. The exhibition centres around the immersive and moving multi-channel video installation The Visitors (2012) and Take Me Here by the Dishwasher: Memorial for a Marriage (2011) a live performance full of romance and humour featuring ten troubadours singing for up to eight hours a day, every day for the duration.

For a country with a population of only 330,000 people, Iceland has drawn a lot of attention recently. It has always had a strong contemporary musical tradition: Björk and, more recently, Sigur Rós, who played at this year’s Glastonbury Festival, are both Icelandic. This summer it played magnificent football, forcing the exit of Austria in a goal in the last minute of overtime: perhaps the most thrilling match in Euro 2016, followed by its win over England.

It is not short of artists, either. Olafur Eliasson is perhaps the most loved of all the Tate Turbine Hall artists as well as having the most photographed work at Versailles, France, this summer. The Barbican in London has now given its main gallery space to performance and video artist Ragnar Kjartansson for his first and long- overdue mid-career retrospective exhibition in England.

Like many others I had first seen Kjartansson’s work in Venice, in the Biennale of 2009 when he was the youngest artist to represent Iceland. Since then I have hung out with Kjartansson and his band of troubadours in a park in Vienna, visited him in his studio in Reykjavik and saw him perform with his musicians in Turin. I also watched a presentation of his video work The Visitors in 2015 in Cardiff, where he was shortlisted for the Artes Mundi Prize (won by Theaster Gates). Although it was not the winner, the selection committee still chose to purchase a work by Kjartansson rather then Gates, so perhaps that was really the winning event.

Kjartansson was born in Reykjavik in 1976 to a family of theatrical parents. His mother is a well-known actress and his father is a theatre producer; his parents split up when he was young. His grandfather, after whom he is named, was a painter and ceramicist and best friends with Fluxus artist Dieter Roth when he moved to Iceland. Kjartansson enjoys both painting and fishing with his father. When I interviewed Kjartansson in Iceland in 2015 he told me that he was brought up partly by the “lodger in the basement” who I later found out was a famous opera singer who taught Bjork to sing. I am sure now that some of what he told me was peppered with artistic liberty, as much of Ragnar’s mythology is a mixture of fact and fiction.

Death and the Children (2002), an early black and white video work, shows Kjartansson as a kind of benign pied piper. Asked to mind some small children by his then girlfriend, he leads them on a tour of a cemetery while fielding questions of mortality wielding a paper scythe, rebutting the children’s jibes about his “fake scythe”, and informing them that it is the “scythe of DEATH.” The children may be older now but they doubtless will not forget their few moments of starring in an early Kjartansson performance.

Ragnar’s first durational performance work, The Great Unrest (2005), was done upon his completion of the Iceland Academy of the Arts and was part of the Reykjavik Arts Festival. Kjartansson found a disused and decaying building in southern Iceland and transformed it both internally and externally, inhabiting it and performing for six hours every day; painting, making music and occupying the space. Although the festival ran for more than a month, it was in such a remote location that only 150 people actually saw the work, but like all great stories the reputation of the performance outstripped the event.

Although Kjartansson comes from a theatrical family his most overt artistic influence is Marina Abramovic with her focus on durational performance art. The difference with Kjartansson, though, may be that, unlike Abramovic, he continually collaborates with a group of musicians and writers, producing works that whilst often melancholic are often humorous – although in quite a dark way.

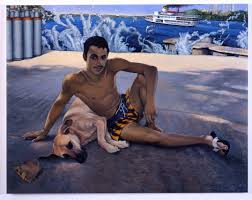

In 2009, Kjartansson set up an artist’s studio in an elegant palazzo on the Grand Canal and for the entire run of the Biennale continually painted fellow Icelandic artist Pall Haukur Bjornsson in his speedos. While the beer bottles mounted the fug of smoke and the loucheness of a summer’s day in Venice infected the atmosphere and the paintings.

Kjartansson’s work often contains music. He has been in various bands since his student days. In his studio on the harbour, a former net mending factory, there is a complete drum kit alongside a piano, and guitars hung on the wall. In the past he has said “I can not breathe without music” and so it is not surprising that Iceland’s rich musical scene has permeated his works.

He has already collaborated with well-known Icelandic musicians Kjartan Sveinsson and David Thor jonsson, both of whom have produced scores for his works and also appear as performers in his large video work The Visitors. Filmed in 2012 in Rokeby House, a beautiful if somewhat decaying estate in upstate New York, the band practiced for a week and then the performance was shot in a single take one afternoon lasting just over an hour. There is a pathos in the group of musicians isolated in various rooms, engaged with each other only through their head phones. Kjartansson lies in a bath with his guitar precariously near the water, his modesty preserved by bubbles. The film – 64 minutes long – played in a small gallery near Cardiff throughout the Artes Mundi exhibition, attracted a surprising number of returning visitors drawn by the extraordinary beauty of both the video and the simple score with lyrics by his first wife, performance artist Asdís Sif Gunnarsdottir. Kjartansson is lost in his own melancholic thoughts, singing the simple almost mantra like words “once again I fall into my feminine ways” before he finally emerges from the soapy water.

In 2014 Kjartansson and his troupe were installed in Vienna in the park of the Belvedere Museum. For a month his team, including his father, inhabited a space performing scenes from a great Icelandic tome. They constructed sets with the help of some local design students, rehearsed and sang, storyboarding and creating an extraordinary collection of objects. They filmed the entire process on video. One day I saw the set for the next day looking strangely pedestrian; when I returned it had been transformed with small painterly nuances of light. I was impressed and asked Kjartansson “When and who did this?” and he showed me his paint-stained hands: “I came in early.”

One of the strangest works in this show is Me and My Mother, a video that Kjartansson made with his actress mother Guorun Asmundsdottir. He has reshot it every five years over a period of 15 years, the most recent in 2015. Standing in the same place, the living room of their home, his mother spits at him. She does not hold back; and the shock of this piece, set alongside the interview I had with him, shows both his unflinching embrace of any subject matter for his art, and his acceptance of his parentage.His parents were also the subject of Take Me By the Dishwasher, a piece created for the New Museum in New York and here reprised with new musicians recruited for their ability to make music whilst drinking large quantities of beer.

When I visited him in Reykjavik in 2015 he told me he was having a difficult time with his ex-wife. There was a tremulousness about him, although the robustness was also visible as he posed in his painting apron for me. He showed me a portrait he had done recently for Vogue of disgraced fashionista John Galliano, who had visited him shortly before. It captures the spirit of the designer, who is likely more used to sitting in elegant salons then the shabby chicness of an artist’s studio in this strange land.

When I flew into Reykyavik a few weeks ago on the longest day of the year, I was coincidentally flying in on the day of Kjartansson’s wedding to Ingibjorg Sigurjonsdottir. The plane was 10 hours late and we landed at midnight, just as the sun was setting. Visiting artists in the city the next day who had been at the wedding all related how happy the event had been – starting at 5pm and ending at 5am in multiple locations. I asked for pictures, to be told nobody took any as “we were in the minute”. Aged just 40, Kjartansson has come of age and with his wit and talent and appetite for investigation there is time for more greatness and experimentation. In the Barbican a large pink neon Scandanavian Pain, an earlier work of 2006-2012, hangs above the entrance, indicating you have come to the right place. Perhaps now though there is a chance to replace the sadness with greatness. Iceland is the place to be at the moment and there is a large piece of it in the Barbican. Kjartansson’s desire to replace “sorrow over happiness” as expressed in God, his semi-cheesy video, may soon change, you never know.

Karen Wright in The Independent